Veteran French director Olivier Assayas has spun his cult 90s film Irma Vep into a sexy, funny and dizzyingly multilayered TV series

Level one, doors opening: Paris, 2022. American film star Mira Harberg is in town to take the lead in a big-budget TV remake of Louis Feuillade’s classic silent serial Les Vampires. She plays its antiheroine Irma Vep, accomplice and muse to a shadowy criminal gang. Mira has a troubled private life, and so does the TV director René Vidal – not least because the shoestring film version he did years ago keeps coming back to haunt him. “Movies are fairytales”, he says.

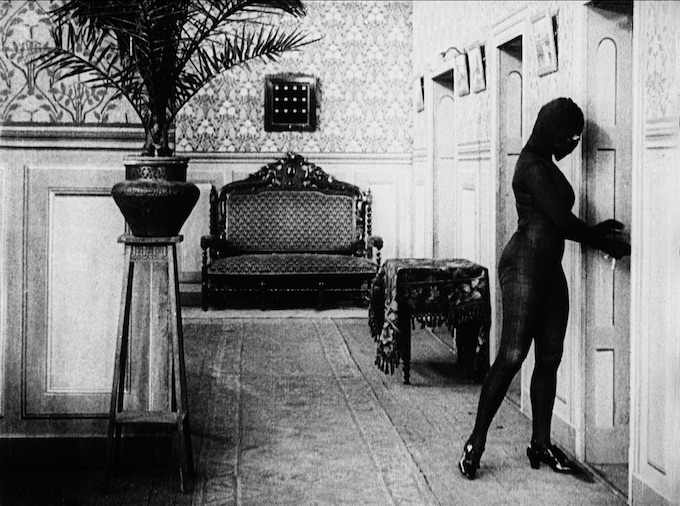

Level two: Paris, 1915. As war rages, production begins on Gaumont’s new serial Les Vampires. With actors and set-building material in short supply, writer-director Louis Feuillade makes it up as he goes along, his plotting a hallucinatory maelstrom of robberies, abductions, escapes, pursuits, guns, bombs, poisons, masks, disguises, aliases, ciphers, spyholes, hideouts and hidden entrances. Star Jeanne Roques, known to audiences by her screen name Musidora, has found in Irma Vep the role of a lifetime. In her black catsuit, Irma is sex and death, menace and grace, a character so duplicitous that her very name has a hidden meaning: in a famous shot, its letters dancingly rearrange themselves to spell vampire. She haunts the screen and the fantasies of the audience, notably the future Surrealists. The phenomenon needs a new word: Irma Vep is the original vamp.

Level three: Paris, 1996. Hong Kong film star Maggie Cheung is in town to take the lead in a micro-budget TV remake of Les Vampires; she will play Irma Vep. The costume designer takes her to a sex shop to find a catsuit; what was silk for Musidora will be latex for Maggie. An outsider on a dysfunctional shoot, she starts to lose herself in her role; meanwhile, director René Vidal is on the edge of burnout, troubled by an overwhelming sense of futility and cinematic sacrilege. Remake Les Vampires? “It’s blasphemy”, he says. Doors closing…

A good elevator pitch is all about keeping it brief, but even one as uncommonly expansive as this would usually only take us so far. In the case of HBO’s eight-episode TV comedy Irma Vep, however, the lift shaft does something very unusual indeed: it operates like a Möbius strip. At the point where the two ends join is the series’s writer-director Olivier Assayas, who also wrote and directed the film of the same title in 1996 – and he’s keen to point out that the new project should not be thought of as a remake; more about that shortly.

Assayas turned 67 earlier this year, and although ruefully admits he now gets his music by streaming, he still dresses like the devotee of record stores he was in years gone by. The youthful enthusiasm is still there, too, an encouraging sign in someone who’s been writing and directing films for more than half his life: after five years as an influential critic for Les Cahiers du Cinéma – with colleague Charles Tesson he was instrumental in bringing a new generation of Asian film-makers to French and wider western audiences – Assayas made his first feature in 1986. Since then he has built a reputation as a stylish, versatile and even radical film-maker, in recent years helming international productions such as Clouds of Sils Maria, Personal Shopper andWasp Network, working with big names including Kristen Stewart, Ana de Armas and Gael García Bernal.

The 2022 Irma Vep is another multinational setup – and multilingual at that, the dialogue evenly split between English and French, plus a smattering of German. Swedish star Alicia Vikander, formerly of Tomb Raider and The Green Knight, leads as Mira-Irma alongside Devon Ross, Fala Chen and Lars Eidinger; the French cast includes Jeanne Balibar, Nora Hamzawi, Alex Descas playing the same character he did in the film and Vincent Macaigne as the endearingly depressive René.

At the outer layer, it’s about the ways life and art work off each other, and the countless ways film-making can go wrong. Mira pinballs between exes male and female, one of the other leads is on crack, the director swings from rage to funk and back again, Mira’s agent wants her to take parts in braindead superhero movies, and the creepy mogul funding the whole thing is only interested in a big sponsorship deal. The pain and strain are familiar from many a film about film, from Godard’s Passionto Tom DiCillo’s 1995 black comedy Living in Oblivion – and, obviously, the 1996 Irma Vep, in which René Vidal is played by New Wave legend Jean-Pierre Léaud, who starred in the classic ‘films fall apart’ movie Truffaut’s Day for Night.

But there’s much more to it than that. Whereas the film was, in Assayas’s pithy summary, “about just one thing, the presence of grace”, the series is not only more elaborate – you’d that expect in a runtime of nearly eight hours – but also far more ambitious; less remake than remix. It’s more focused on filmcraft, showing methods and equipment that have brought huge changes to film-making since 1996; it’s also philosophically invested in what our age of platforms and networks has done to the moving image – the characters are forever watching snippets of Feuillade on their phones – and what the differences might be between a film and mere content. What is a TV series, anyway? René Vidal insists that his is a film in eight parts, a definition Assayas says he endorses – and indeed, the first three episodes of Irma Vep were previewed at the Cannes film festival in May.

For Assayas, there’s also a personal dimension that takes the series inwards as well as outwards. The earlier film was a love letter to its star Maggie Cheung, and she and Assayas were subsequently married for three years. The 2022 René Vidal, more pointedly a surrogate of Assayas than the film version – Macaigne practically impersonates him – is still haunted by memories of his Hong Kong star and ex-wife Jade Lee, and the scenes in which he remembers her are among the most poignant in the series. (A serendipitous echo: director Mia Hansen-Løve, to whom Assayas was married for 15 years, recently released Bergman Island, described by Jason Solomons in this newspaper as “a film about a film-maker and her film-maker partner, writing a film about a film-within-a-film”.)

In late 2020, Assayas published an essay titled ‘Le temps présent du cinéma’ (roughly, ‘Cinema in the Present Tense’; it’s available in full and in English translation on the excellent film website Sabzian). “In films, as much as in any work of the mind”, he wrote, “it’s our unconscious that’s at work, we merely open the doors to it” – and that brings us back to Irma. Is she a tutelary figure, a dark patron saint? The series named after her seems to reclassify film itself, not so much a medium as a mycelium, an enchanted network of filaments branching, joining, running for miles, dense and sophisticated in ways barely understood, a living force with its own occult ways. There was always something suspicious about the fathers of cinema being called Lumière.

But never fear: Irma Vep is no descent into the navel. It’s consistently playful, often romantic, sometimes kinky or raw; it’s satirical but sweet-natured, beautifully filmed and often extremely funny. The performances are superb, especially from Lars Eidinger, who steals every scene he’s in; and Assayas’s record store past was clearly worth the time, because so is the soundtrack, with original music from Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore and a gloriously eclectic playlist of tracks that starts with Mdou Moctar on the opening credits and goes all the way back to the Renaissance.

There’s also much pleasure to be had in the steady supply of what the French call clins d’oeil (winks): a 1915 cartoon of the masked Musidora in the opening credits, William Etty’s 1840s painting ‘Musidora the Bather’ in the background of a rehearsal scene, a tote from Bologna film restoration festival Il Cinema Ritrovato, or a glimpse of a book by Gilles Deleuze, the one film theorist Assayas says he rates. Assayas also has fun with droll reenactments showing Feuillade at work or Musidora soft-soaping the chief of police, who has shut down production on grounds of indecency.

For all the setbacks and sideswipes in the storyline, it’s an enterprise that exudes optimism and a wonderful sense of the absurd – and you don’t need to have seen the serial or the 1996 film to enjoy it. The worst one could say is that it might turn out to be too ambitious for its own good, and that would be a pity: because this multilayered mashup of comedy and serious ideas – call it a millefeuillade – is perhaps Olivier Assayas’s most radical, riotous and brilliant film. Series. Film.

NOTES

This feature was published in the 7th July 2022 issue of the New European.

All eight episodes of Irma Vep were broadcast in the UK on Sky Atlantic.

To read more of my published work, click here.

The photo at the top of this post shows Alicia Vikander in the title role of Irma Vep, and is © Warner Media. The second photo shows Maggie Cheung in the title role of the 1996 film version, and is © Vortex Sutra. The third photo shows Musidora as Irma Vep in Les Vampires, and is © Gaumont.